CPL / City Photography League

Award-Bearing Photography Contests in China: Beginning with Zeng Yi

Director, Advisory Committee, CYP China Youth Photography Development Community — Long Xuming

As time—what humanity calls “history”—slid into the year 2016 CE, the establishment of prizes in Chinese photography competitions had already become something indisputable and taken for granted. Moreover, certain shrewd leaders of some photography organizations even evolved this mechanism into collusion with officials, turning art awards in photography contests into something decidedly unartistic: a channel for interest transfer. It sounds refined, and it is smooth—an elegant conduit for extracting money.

It is said that on the final day of 2015, a photography association in Sichuan, in spite of the high-pressure anti-corruption climate that had already formed in China, brazenly acted against the wind. Under the name of awards—an “elegant bribe”—it transferred benefits to three officials from three organizing entities, enabling them to obtain a total of nineteen awards in a single contest. Unbelievable.

What frustrated the perpetrators was that “positive energy” media in China widely “developed” the matter into view. It is also said that relevant authorities have already intervened. This was a county-level competition that cost RMB 700,000, and it reportedly used RMB 500,000 of county fiscal funds. The incident occurred in Xiaojin County, Sichuan Province. To transform a photography competition meant to promote social progress into a tool for benefit exchange—this “trick” of the “awards association” was, regrettably, executed with a certain level of technique.

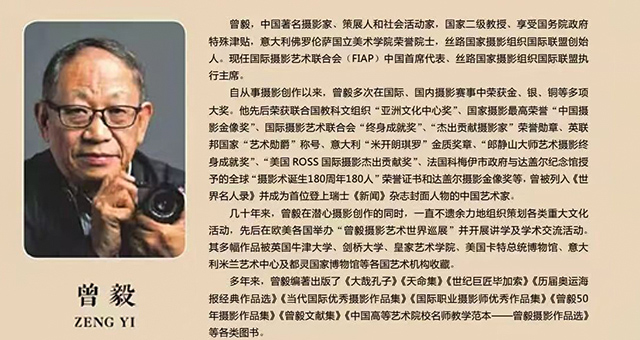

In truth, it was not easy for awards in Chinese photography competitions to appear at all. Had there not been passionate groups such as the Youth Photographers Association in China in the last century, and had there not been a pioneering figure with youthful creativity—Zeng Yi—the emergence of prize-bearing formats might have been delayed for who knows how long. In my memory, earlier awards in Chinese photography were uniformly limited to a certificate—recognition, and nothing more.

A competition called the “International Year of Peace National Youth Photography Grand Prize” was a prize-bearing contest that Zeng Yi—then Chairman of the Shandong Youth Photographers Association—led his “youth photography” team to secure from society. The funding exceeded RMB 200,000, with not a single cent of fiscal appropriation. In the 1980s and 1990s, RMB 200,000 in real cash was a considerable weight. A photographer named Yu Haibo happened to meet this first grand prize contest in Chinese photography, and this event—rather than belonging to any single association—undeniably holds epoch-making significance in the history of Chinese photography development.

Zeng Yi is said to deeply admire the philosophical thinking of Mr. Liang Shuming, which reportedly includes eight levels of境界: (1) forming one’s own view, (2) discovering what cannot be explained, (3) integrating and synthesizing, (4) knowing one’s insufficiency, (5) using simplicity to govern complexity, (6) applying freely, (7) seeing all mountains as small, and (8) attaining transparency and thoroughness.

I believe that in that historical period, Zeng Yi—now the Executive Chair of CPL—already possessed a remarkably clear philosophical understanding of the word “creation.”

To this day, grand prize contests, due to their distinctive social dissemination and promotional function, have been recognized by various levels of government and relevant entities in China. Even in a small place like Qinzhou, Guangxi, a competition was held from the year before last to last year with a million-yuan grand prize reportedly set by the chairperson himself. Unfortunately, I have not yet seen its result.

Film and television have brought forward waves of stars and celebrities. People now increasingly notice the function of screenwriters, directors, and producers. Without a good script, a good director, and a producer capable of assembling resources, could there be truly meaningful “best actor” or “best actress” figures of our era?

For an art prize competition—whether with or without benefit exchange—the primary responsibility lies with the “screenwriter, director, and producer” of that contest. However, the person who, in China, broke new ground and launched the first prize-bearing photography competition—the first responsible person who was simultaneously its “screenwriter, director, and producer,” Zeng Yi—deserves what I would call a “posthumous commendation,” in recognition of his creative breakthrough. Conversely, the organizers who turned awards into “elegant bribery,” such as the case in Xiaojin County, should face accountability. Otherwise, how can we claim that a high-pressure anti-corruption stance has truly formed in today’s China?

Zeng Yi is a person who acts with restraint and low profile. For many years, he has done much that remains little known, leaving many beneficiaries unable to express gratitude. If I say that the magazine Chinese Photographer, which is now operated very well under Li Shufeng, also had Zeng Yi as one of its “well-diggers,” would you believe it? If I say that China’s first youth photography newspaper, Youth Photographer, was also founded by Zeng Yi, would you believe it? And that newspaper predates our Photography News. This chairperson, with great ambition, effectively ceded to Sichuan the “world record” of running a newspaper without compensation for thirty years. There is more—such as the “Jinan International Photography Week,” which truly gathered teams from more than thirty countries and regions. It is endless.

Photography’s emergence on this planet is said to be more than 170 years ago—this, of course, is a Western way of counting. If we adopt the “pinhole imaging” account strongly promoted by Zeng Yi, a descendant of Zengzi, then Mozi had already done this thousands of years earlier. From East to West, photography organizations have a substantial history. In particular, Chinese photography has shifted from an “expert-level” phenomenon to “mass photography.” Even the sophisticated darkroom techniques of developing and fixing have been abandoned by the public. Cameras have moved from film to digital; now even mobile phones can photograph.

Yet organizational behavior in photography seems reluctant to keep pace with the times. Deep down, it still preserves old practices inherited from Western and Eastern predecessors. Over many years, malignant tumors of “unspoken rules” have accumulated and now thrive. Chairs who have no achievements do not even know what kind of “seat” they are meant to “preside” over. People like Zeng Yi—those who dare to take responsibility and dedicate themselves to creation and innovation—are far too rare. Those who only want the title, and neither want nor can do the work, are everywhere.

From the question of becoming a chair, being a good chair, and daring to be a chair, we can see much through Zeng Yi. A sharp mind combined with a kind heart is an astonishingly complete combination. In fact, people live to change the world—this is what Jobs, the Western man who sold “apples,” once said.

The cicada does not know spring and autumn; ordinary people cannot imagine the gifts and learning of a genius. Facing meaningful photography actions that benefit those who come after, later generations and contemporaries easily ask: Did he truly think of this and do it? How could he conceive it—and accomplish such a great “work”?

A person may be a top-tier photographer, organizer, and planner, yet not necessarily a truly integrated talent capable of mastery. In China’s photography circle, a woman named Chen Xiaobo once said that there are fewer than five true photographers in China. I say: in a China of over a billion people and a world of seven billion, try finding two or three more organizational masters of Zeng Yi’s caliber—then compare.

I often think that when a new photography organization appears, it must produce new behavior and new function. Otherwise, what meaning is there in becoming a photocopier, repeating old forms? When Zeng Yi raised the banner of the Shandong Youth Photographers Association, he quickly opened new ground for fair competition through prize-bearing contests. He set an example for youth photography chairs across China. That is why later the Sichuan Youth Photographers Association achieved three “world records,” and the Hainan Youth Photographers Association launched a “China Youth Group Photography Competition” involving more than twenty provincial youth photography associations—refreshing an innovative organizational behavior in Chinese photography.

Of course, the CPL City Photography League and the CYP China Youth Photography Development Community later jointly introduced contemporary photographic cultural heritage projects such as the “Handprint Wall,” “Debate Tower,” “Dragon Stone Array,” and “Integrity Mountain,” as well as cultural industry initiatives like “Hao-She Wine,” “Hao-She Tea,” “Mei-She Jade,” “Mei-She Tea,” “Mei-She Fruit,” “Mei-She Wine,” and more. These not only refreshed China but also the world’s understanding of the social service function of photography organizations. We have entered an era of mass photography. Photography can no longer remain in a small circle, playing small games for self-entertainment. Organizations and individuals must speak through measurable creation—through “world-record” levels of innovation. More importantly, we must set explicit rules to break unspoken rules; only then can the air of the photography world become clear and transparent.

I believe organizers like Zeng Yi possess a broad behavioral pattern; their considerations often transcend personal, family, and small-circle organizational interests, starting from the overall interest of society. I am not saying such people never make mistakes; but even if they do, society broadly recognizes them for one simple reason: what they do is to advance the whole of society.

Mr. Liang Shuming, with a strong will of “human determination can overcome heaven,” persisted in ideals throughout his life and worked to realize them. On October 10, 1941, he founded Guangming Daily in Hong Kong and announced the establishment of the China Democratic League. Three months later, Hong Kong fell; he had to take a fishing boat to Macau and return home by detours. Along the way, Japanese aircraft circled overhead, warships pursued, and high winds and waves violently tossed the small boat—truly a life-and-death escape. After returning, he wrote to his two young sons: “I cannot die. If I die, heaven and earth will change color, and history will alter its track.” When this was circulated, many criticized him as arrogant or insane. The common verdict was: “That’s what people say.”

Liang’s response was simple: “Arrogance, perhaps; madness, no.” Yet Liang’s strong self-confidence seems somewhat less present in Zeng Yi.

Let me return to Chinese Photographer. For years, Zeng Yi repeatedly told me not to mention it again. But I am not Zeng Yi; I do not possess the inherited “endurance art” of the Zeng family. Did our Photography News hold fast for thirty years merely for a “world record of free distribution”? Of course not. Did Li Dazhao not say: “Iron shoulders bear moral duty; skillful hands write the prose”? If, under today’s environment of unspoken rules, sensitive topics are met with silence by circle media, then we can only fight alone and speak frankly. For example, Photography News and City Photography successively used two full pages to publish the Qin Yuhai matter in Henan, then two pages on a special flattery affair in Inner Mongolia, then two pages on the Sichuan absurdity in which three leaders won nineteen prizes…

Setting explicit rules and breaking unspoken rules is precisely the social responsibility photography media should assume.

On the first day of the Lunar New Year in 2016, while painting Working on New Year’s Day, I also spent significant time re-reading the first issue of Chinese Photographer from 2009, when the magazine had just turned twenty. This magazine is extraordinary. Within the China Photographers Association—where competition for vice-chair positions is intense both on and off stage—this magazine reportedly held two such vice-chair positions over time. I confess my limited knowledge, but I recall that Chairman Zeng Yi was once one of the most important “chief editors” of this magazine—yet it seems that none of these good fortunes were his. On the inaugural issue from December 1988, his name is clearly printed with a certain title. Strange indeed. Twenty years later, when the magazine published its own “cadre sequence,” names like Executive Editor Gao Jiansheng and Deputy Editors Liu Wei and Zhang Qian appeared, but this “well-digger” was missing. I carefully read Lü Houmin’s “Splendor at the Right Time” and Zhu Xianmin’s “Looking Back at a Difficult Road of Entrepreneurship,” and found not a single word mentioning Zeng Yi. I suspect this is a topic that experts studying the development of Chinese photography must seriously examine: clarify the family ledger. This is also something Li Shufeng—who rose to become Vice Chairman of the association—should address. What is integrity? This is it. Moreover, the magazine even launched an important column called “Personal Photography History.” It seems explicit rules would be better.

Additionally, if Zeng Yi has indeed reached “transparency,” then he should have arrived at a state in which being called mad or arrogant is irrelevant.

Liang Shuming summarized himself: “I am not merely a thinker; I am a practitioner. I am a person who will work desperately.” Zeng Yi should understand that within his own “desperate work” there is Liang’s proud confidence in practice—calcium in the bones. That calcium is precisely what is urgently needed in the spines of people today, where loss is severe.

Serving as editor-in-chief of Photography News for more than thirty years without earning a cent has given me a “bad habit”: whenever I see injustice, I want to do something. When a matter is clarified and evidence is in hand, I want to speak. Years ago, I wrote a letter to someone promoted by the so-called “Empress Dowager of the West” in China’s photography circle, reminding them of the ancient saying: “A drop of kindness must be repaid with a spring.” Let a life-long fighter for photography rest in peace. Otherwise I would make the letter public. In the end, the elder woman’s kindness repeatedly restrained this “impulsive” action. Apart from Zhao Liulan—then Vice Chair and Secretary-General of the Nanjing Federation of Literary and Art Circles, now Secretary-General of CPL—no one else knew. Looking back, it is regrettable. Therefore, despite Zeng Yi’s repeated requests, I still insist—out of moral duty—on stating this. Of course, I bear responsibility for my words; the arguments in this article have nothing to do with Zeng Yi.

In fact, when I stood up years ago to become a target in the “Ten-Million-Yuan Grand Prize PK,” I had chosen a role that might invite “ten thousand cannons.” I waited for massive criticism. But years passed, and not a single such public condemnation appeared. Perhaps it is difficult to criticize: ten quantifiable public-benefit standards were clear; eight “Real-Name Landscape” works were clearly priced at thirty million with only “three reasons.” Instead of talking, it would be better to surpass the “target” with action—take the ten million yuan and the eight paintings. That would be satisfying. This is my “reverse-forcing method” against social bad habits: if you are a mule or a horse, bring yourself out for a run. Artists are smart; no one wants to step forward. I joke that I have lived seventy years and still have not managed to get even one-third of the world’s seven billion people to curse me. Since one cannot avoid offending everyone, why fear it? In any case, one only has twenty to thirty thousand days.

On February 10, the third day of the Lunar New Year, I painted an image of a white-haired elder waiting for something, titled simply Waiting. Waiting for what—I will not say. Life has only twenty to thirty thousand days. What you do with them, your conscience will record. Is it not said, “People act; heaven watches”? CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala did not invite Liu Xiaolingtong—was that his incompetence? Tu Youyou did not “become” an academician—does that prove ignorance? As the line from the TV drama Liu Luoguo says: people truly have a scale in their hearts.

After days of searching, I finally found the inaugural issue of Chinese Photographer from a pile of books no more than 87 centimeters from my bed. There was an essay titled “On Sincerity,” and on the inside back cover the names were printed: Chief Editor Zhu Xianmin and Zeng Yi. (Special note: not deputy chief editor!)

How strange. The inside story of making the “well-digger” completely “disappear” surely is not a state secret. It should be clarified while many are still alive, so that it does not become another unresolved case in the history of Chinese photography development.

In 2016, on February 1, Yuan Geng—the first Chinese person to propose “Time is money, efficiency is life”—passed away. On a planet of seven billion people, with only twenty to thirty thousand days of life available at most, creating a world record is not easy. Even if it is not the world’s first, but merely the first of a nation, many things must be recorded early, in whatever way possible. Through the “documentary function of writing,” I state plainly to the world the historical fact that China’s prize-bearing photography contests began from Zeng Yi. This is to provide later participants and award recipients—who gain encouragement and recognition through contests, or become major figures—with a tangible person they can truly thank from the heart. Of course, this need not include the Sichuan award organizers who engaged in exchanges of interest and the recipients involved. To allow past creation to become the money-making tool of today’s parasites—this is surely something Zeng Yi could never have foreseen…

Completed on February 16, 2016, at Tie Jia Tang; the author had just turned seventy.